Whatever lives has meaning and whatever has meaning lives. ( C. Geertz)

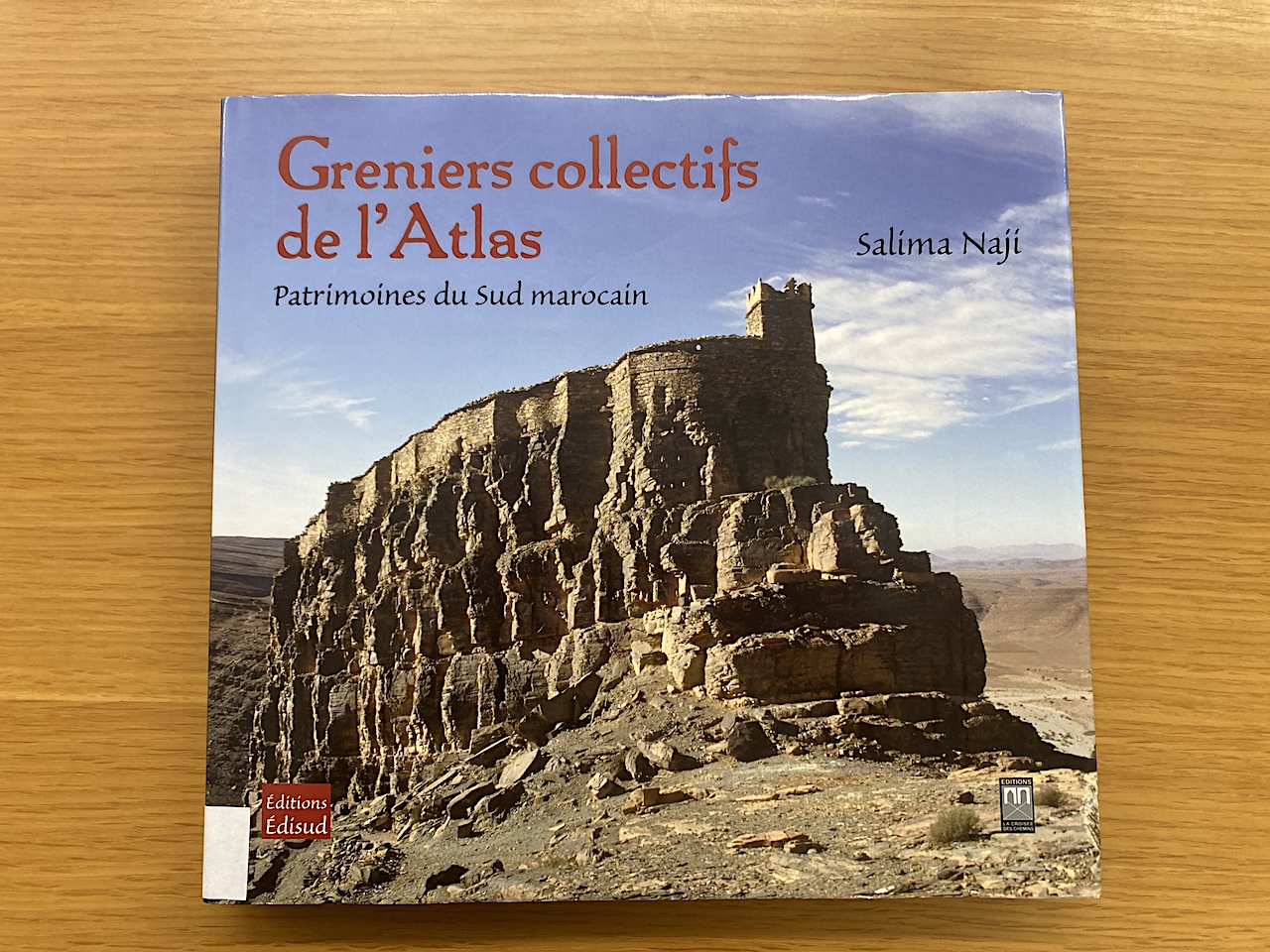

Years ago, strolling around Gueliz, something in a shop window caught my eye. It was a book store and the cover of the book in question portrayed a fortress ( or a castle ?) strung up on the top of a bluff. The proportions, the angles, the walls, the way the edifice seemed to taper out the bluff itself – uncanny. This can’t be real – it’s the first thought that crossed my mind. The second: if it is, I have to see it in person. But how to find it ? Where to begin ? Well, fortunately, books have authors. So I started with that and some months later and 500 kilometers southwards, I saw the place and met the author. That was almost 10 years ago and little I knew back then that the agadirs/ ighrems of Morocco would become staples on our private Morocco tours.

Time hasn’t dimmed the feeling: I’m as baffled now as I was back then. And while most visitors to Morocco are familiar with the kasbahs, very view are familiar with the agadirs ( granaries). Yet, they are much more than the sum of their parts: part archaic banks, part sacred spaces, part defensive fortresses, part architectural genius. They are repositories of culture. No, not museums. Breathing, living places, even when they appear to have fallen prey to decay and the passage of time.

Every year my wanderings through Morocco’s draw me back – is it the baraka of the saints that have trod them centuries past ? Only their cobbles could tell. This year ( 2024) bears a particular significance. After the earthquake in 2023 and the torrential floods of 2024, it gives me great joy to see the granaries of the Anti Atlas haven’t budged. Credit to this lady, architect – anthropologist Salima Naji, that is behind the restoration of most of them, but also to the generations of maalems and anonymous architects that have erected and preserved them during the ages. Through this interview, we hope to give them credit and shine some light on something that truly makes Morocco unique.

N.B. The interview was lightly edited for readability. The words ‘ighrem’, ‘agadir’ , ‘tagadirt’ or ‘granary’ are interchanged in the text, but refer to the same object. Photos taken by David Goeury & Cristian Martinus from 2012 to 2024.

ST: Someone once said that if there is ‘something that binds humans across space and time, it is their ability to create meaning’*. What is the meaning of collective granaries in Morocco?

Salima Naji: This is not a simple question to answer. Collective granaries are first and foremost a question of comradeship. In the face of hunger, in the face of life. We witness a complex architecture built with very scarce means (proximity architecture, we collect and employ what is within reach) to secure what the community generates to feed itself. We must not forget that for centuries society was not immune to calamities: famines, droughts, diseases (typhus, cholera, etc.), inter- tribe wars (for survival), etc.

ST: In medieval Europe, the church or cathedral played the role of repository of culture. It seems that in the Moroccan hinterland, this role has been played by the granary. Is it still the case ?

{ Read: Book a private tour of Morocco that includes some of the granaries of the Anti Atlas}

SN: It is possible that some granaries even precede the arrival of Islam. They are not settlements per se (places where people live), but serve a much higher purpose. They are also sacred, despite not serving as a place of prayer. They are called “zawata”, small zawyas ( monasteries), and those of the Ayt Bou Guemmez were built on the tomb of a patron saint.

They are also eternal landmarks in a world caught in perpetual change. Every time I return to Amtoudi, I am taken by this feeling of eternity standing opposite its agadir, and I like to think you feel the same. They stand as if outside of time. The etymology of the word clearly refers to the idea of a primitive wall, to the idea of an enclosure, a fence, a protection, to its primary role as a refuge. We know that the first granaries were simple enclosures, most often reduced to a barely masoned cave or a rocky spur hedged by a wall. These words, which all belong to the same linguistic roots, mark therefore the birth of a heritage.

ST: All this would explain that this feeling of the eternal prevails even when the granaries are in ruins, or even almost erased ?

SN: Granaries are also a whole crowning of human effort. And what an effort… Very small communities have sheltered their grain to ensure the survival of their group over time in an arid climate where they have to wait for rain for years. These granaries are built over decades, over two, three, four generations, one or two centuries, sometimes more. The granary is a receptacle. The spiritual value of these places is enormous. Sacred places, it’s what they are. Places unbeknownst to the general public, yet truly representing a quintessence of architecture and spiritual values specific to the Kingdom (of Morocco)…

ST: How are they different from kasbahs? What do they store? Are they more than just archaic banks?

SN: The essential difference lies in collective heritage versus private. The granary is collective. The kasbah is a local lord who at a given moment in history extracts himself from the community to build his private residence. It is also why these granaries move us – they embody the power of the group. Faced with adversity, misfortune, the hazards of life. It is also an architecture that yields life lessons: what is the most important thing, which is eternal, essential ? Respect your fellowman, witness your reserves increase, shelter it. Feed yourself, protect yourself: survive! While the kasbah collects what was built for the individual.

There is this question of equity and solidarity that I spoke about at the beginning. For a long time, the kasbahs were built pegged to the ksar (enclosed stone/adobe village). Kasbahs boomed under the colonial occupation when a few local pashas who sided with the French, such as the Glaoui family, the Goundafi, etc. In the palmgrove of Skoura, one such example is the Kasbah of Amridil (which appears on the 50 dirham notes). There are also bloodline kasbahs, of a clan, we see some in the Middle Atlas, in Ait Bouguemez, etc. which are used to store fodder, many still intact.

ST: So far, you have restored many fortified granaries and ksars throughout Morocco. Mosques, minarets, synagogues, fortified tagadirt’s or Kasabah residences, “tiny heritage”…

SN: It is so tedious. So long, demanding. I never ask for a fee, or else we could not achieve the completion. People do not realize, it is not enough to muster masons, you have to supervise, support, inspire. Make sure that everything is understood. Stay on site. Control the quality of the materials, the completion, the people. You have to pay over time these highly qualified maalmines ( master craftsmen) and stave off all third party interferences… I talk in detail in my book ( Architectures du bien commun) about the invisible roadblocks, the petty corruption, the ill- will: it is easy to derail a project. When you take it all into account, we are lucky to rescue these sites. It is really difficult.

ST: How did you start all the way in the beginning and where did the idea come from? What drives you?

SN: What made me undertake these restorations is that in each case the place was very important for the villagers. I didn’t ask myself any questions – for the first one the coincidence made that I had just received a family inheritance. I chose to restore everything, but WITH the people, and FOR the people.

It’s still the same case presently ( I just financed the roofs of the attic of Adkhss granary again with my own funds). My first job was in 2003. And then there was the torrential rain of 2004: I was doing my doctoral research in the field, I was with the Akinou family to whom I remained very close. Suddenly, one night of torrential rain, a section of the attic of Aguellouy granary was washed away.

If you want to know the whole story, here it is:

Lahoucine Aguinou, son of Haj Abdellah, president of the local association, took legal charge of the situation to organize the restoration in compliance with the law. I offered to cover the workers’ wages. Many refused, arguing that the attic is “their ancestor” and that they must therefore restore it free of charge. It was sublime, frankly I still hold them in the same esteem. Haj Abdellah is a true grandfather figure to me. It has created bonds for life.

Coming back to Aguellouy, it was 2003-04, difficult because the attic was cramped – Aguellouy is an attic clinging to the cliff where all the space is saturated, the corridors and huts are tangled on nearly five vertical levels, leaving little space to handle the materials. Some floors have collapsed on top of each other, so everything had to be emptied, sorting the material that is stored nearby as best as possible: stone, wood, earth are put aside in different compartments to be reused. We spent a lot of time moving materials into a series of boxes, to free up space and rebuild, then transfer tools and materials again into a new restored and cleared space, to advance box by box in the attic.

The main collapsed box had to be reassembled from its foundation base to carry all the levels up to the upper terraces. The actions were very delicate. A team of master masons was spontaneously formed around the project. This small team was made up of volunteers known for their probity and professionalism. They all lived in the village, Abdellah Baya, Lahcen Bamoh, Mohammed Amarir, Hassan Ourah, Brahim Aderdor, the anonymous heroes of this project. They are the same ones with others that I found in 2014 after the torrential rains that had washed away the facade of the attic. For me, it was a seminal experience.

I have a debt, an immense debt to these communities who formed me, accepted me as I am, who shared everything. Despite having followed advanced studies in architecture, I nevertheless learned a lot on these construction sites. Moreover, I do not receive any remuneration for these restorations, but that doesn’t bother me. It must not disappear and it is also thanks to people like you, who support us regularly. But to come back to your question. What motivates us? Why save? Well, the feeling of gratitude and also to reward the people who keep them alive. For the people this granary is essential, as a tribute to their ancestors. Moreover, they call it ‘our mother’. This typically Amazigh idea, of the mother, of the matrix, the earth also, which nurtures us all.

ST: Was there something particular in building with adobe that drew your interest ?

SN: Yes, my first works in 1993, took place in the pre-Saharan valleys, Draa, Tafilalet, Todgha, Gheris, etc. If I may digress, a decisive moment for me was being able to visit the earthen villages of Gao, Djenne and Timbouctou in Mali in 1995. I stayed there all summer, I lived in Gao for weeks, as well as in Djenné, with the villagers, in “traditional” houses. It was there that I became aware of the vitality of earthen architecture. On returning to Morocco, a few months later, I had acquired the deep conviction that I had to take care of this earthen heritage, because it wasn’t extinct. Dormant certainly, but alive.

The first kasbahs of the palm grove of Skoura were restored as guest houses by individuals by Mr. El Ouarzazi, the first around the years 198-99 with Kasbah Timbouctou then a trend took shape and kasbahs were gentrified all over, Ait Ben Moro for example, and then the patching- up of Kasbah Madihi of Skoura which is relatively a very recent Kasbah.

This idea of living heritage is of utmost importance for me: it should not become a museum. It has to be invested, inhabited, used, not gentrified or reduced to a profit-or-loss vector: the heritage should remain in the hands of the inhabitants, despite the shrewdness and greed of a certain kind of tourism. It gives meaning to everyday life to the denizens.

Inspiring Morocco Private Tour Ideas & Travel Programs

Explore a handpicked selection of tailor-made Morocco private tours designed to spark your next adventure. From romantic escapes to cultural journeys, find the itinerary that matches your dream experience.

Feathers, Ivory and Gold

Honeymoon in Morocco

Land of the Setting Sun

Marrakech to Fez via Sahara

Salt and all that Glitters

Then came to me the idea that I could be useful and this vision of saving places with people and for people was born. Mixed with the feeling of loss, an urgency to rescue and of vitality, of things still very much alive. This is why I pine for those wares and manufactures that I recall part of everyday life as a child, and that nowadays are stowed and piled inside shops as souvenirs. Women wore all their jewelry and abodes still boasted their wooden doors, and more crockery or textiles than today. The idea of a heritage that can survive is essential. A living heritage.

ST: What is the difference? Between a living and a fossilized heritage?

SN: A living heritage is very precious because it can be awakened and embody something substantive for its community, unlike a public museum, a disembodied space without a soul. It is said that it has lost “rouh”, its soul, its breath. The place is dead. That is the case with the Canary Islands. There, 90 % of the Berbers were massacred by the Conquistadors when they settled on their islands in the race to America around 1492. They have been in disuse for over 600 years.

In Morocco, where some granaries are still used, still useful to their community, they are very much alive. It is fortunate to grasp how they function, to decipher the solidarity networks between various linked granaries. Our granaries must be saved for this reason too: because they are vital to their communities, still in use. When they are no longer used, for 10, 20, 30 or 50 years, that is to say when we still keep the memory of their usage, it is easy to retrace it. When more than two generations have passed, it is different: we must reflect, question. There’s the matter of reconverting, a very delicate one. There are ways to render these agadirs self- sufficient, at least partially. We can preserve the beehives, the pilot project we set up in Adkhss n’Arfalen with the honey, that linked it with the food production.

ST: How old are these granaries and how have they managed to face the passage of time ? How many of them are still active? How did the masons achieve their architectural feats without any formal education or architectural studies?

SN: There was an exhibition at MOMA in 1964 and a book published in 1968, “Architectures without architects” by Bernard Rudofsky. They revolutionized modern architecture. The school of architecture is the school of life, not academies. The granaries or ksours (plural of ksar) are built by peasants. Sometimes there will be a man or a tribe who will stand out from the community and display more skills and a talent that will morph into a vocation in its own right, and he will move from place to place. But do not mistake this with the norm. These mountain people knew and still know how to build.

The idea of maalem (master craftsman) appears quite late in the rural world. The modus operandi differs from the cities. These craftsmen will then be employed for details such as the door, the mosque or the exterior wall of the granary. Even today, when I employ some maalems-farmers they stop working on the construction sites at harvest time or sowing. Because deep down they remain farmers aware of life cycle.

And applying in construction principles of common sense and what is called chkoul in Arabic ( “harpage” in French). On the angles of the constructions to be placed at right angle for more durability. This principle is known to all, here ( in Morocco) it is a common word (chkoul) while in Europe it is highbrow lexicon. These are ancient notions that are taught since childhood or adolescence because we live in exposed ( to the elements) latitudes, always in need of help: help to patch a roof, a wall. The men learn on the job.

ST: In this case, how can we explain that attics on several floors (where there is no cement or concrete) do not collapse?

SN: But cement doesn’t last that long! After 60 to 80 years, without maintenance, it collapses. Look at the Genoa Bridge which collapsed all of a sudden. Each building has a life cycle. Buildings built in stone last thousands of years, look at Greek architecture. Our own earth and stone architectures, they are very solid and often several centuries old. They need to be preserved.

The granaries, they were built over generations. To last. And so they employ very intelligent devices to hoist earth, stone and wood atop (sometimes 15 m high), similar to vernacular techniques in Yemen, Turkey, Switzerland, Japan, etc. Vernacular teaches us the essential. There is acquired, deep know-how, worthy of sophisticated engineering in traditional architecture. Placing a beam at a right angle. This is an essential detail in all constructions.

In a society where men take on responsibility as teenagers, they are not going to take chances, they will build well with principles based passed down from father to son. We are on my construction sites on a co-apprenticeship, I learn certain techniques or certain rules of the art, and I teach them how to make lime for example. Unfortunately, in modern Morocco , the know- how dissipates. That said, even children in these regions are taught the basics at a very young age and subsequently building turns more intuition than theory.

ST: How many of these granaries are still in operation?

SN: About a hundred, at the time of my PhD ( 1999). A first category, cut off from the main routes. There are ‘seasonal’ granaries, where locals store bags of barley as they come down from the high mountain plateaus in winter. Then there are the storage granaries I mentioned before. There are also ‘women’ granaries, there where the rural exodus was too strong, where these women still store fodder for the dry season. The nature of the usage changes. Also, when there is a link with the local zaouia (roughly the equivalent of an abbey or monastery in Islam ), things will be stored to give alms to the poor, the needy, orphans for the local Eid ( El Kebir – most important Muslim feast) or moussems (village festivals).

Moreover, it was also a common practice in the houses of the medina of Fes or Marrakech where families gave alms this way – in grains. Nowadays, this solidarity is still manifested in the saint’s vat, inside the granary. What is it? It is a container where everyone can contribute to help others, inspired by, or recipients of the baraka ( sacred grace) of a local saint.

What is extraordinary is that I sometimes came across granaries that were almost completely abandoned but where the saint’s vat was still brim full. We must not ignore these regions were often subject to cycles of natural disasters, famines, droughts, typhus or locusts and the granary represented a protection. Moreover, the Sultanate in Morocco inherited the institution of the “Berber Agadir ( granary)”.

ST: Do you mean that granaries are historically linked to the Moroccan monarchy ?

SN: Strength is projected from the granary in its way of being united in the face of adversity, war, famine, crisis. The makhzen is like the granary a model of social cohesion, a granary manages the interests of each in the interest of all. This form of particular government ruling over the treasury of a community has thus been brought closer to the Makhzen, the Moroccan “central power”. In Meknes, for example, one can still visit the wheat granaries built by Moulay Ismail, the Hri souani, built not for his personal consumption or that of his court, but for the people in the event of a subsistence crisis. This is well known to Moroccan historians. The Cherifian sultans chose this model of immemorial, sacred and patrimonial belonging to govern well. The granary is this heritage. The grain is sacred…

ST: Should we consider a kind of national denomination, like national monuments to benefit from the preservation of this heritage, not to mention UNESCO or others?

SN: I am not that convinced by the examples of the past, and I am referring to the development of the Kasbahs (Kasbah Ait Benhaddou was designated a UNESCO site in 1987) from the moment we wanted to promote them for tourism. It is a caricature. Tourism should be something for the long term, not makeshift. Efforts cannot only be financial, but also educational. A tourism actor, travel agency, tour operator or other, should travel a minimum and then ask themselves the question: What do I know about my culture to be able to impart it? Why not educate people from these regions, those passionate about their culture and who would be able to convey it to visitors ? Not trained by private actors, but by the State. For my part, I advise locals to always form groups, collectives, precisely to better balance individual or private initiatives that could harm the community.

ST: What makes the area located between the Atlantic coast, Djebel Bani and Oued Draa unique compared to other regions of Morocco in terms of culture? Do you know of another region of the world where this is given ?

ST: In Oman and Saudi Arabia, but they are no longer inhabited. Visiting these places fortified me to keep on, despite the difficulties. Maybe in Turkmenistan and around, but these are countries at war. In Mali too, the whole Dogon country, but it is no longer possible to visit them. Henri Terrasse’s book on the Berber Kasbahs published in 1938 testifies to the fact that this part of Morocco was still not ‘pacified’. This may have preserved this isolation, in contrast to the large imperial cities and the north of the country. And so even if in recent years, the roads are now tarmacced , it is still largely ignored by visitors.

ST: You say in your book: “Provided we advance cautiously and are infinitely respectful of people and territories, this diversity allows for quality sustainable and cultural development, capable of satisfying, with dignity, not only the inhabitants but also the visitors“. How do you see this happening? How could visitors interact with the agadirs in a way that enriches themselves culturally while preserving the dignity of the inhabitants and the authenticity of the vernacular?

SN: Thanks to agencies and actors like you. It is a niche heritage, fragile, where crowds do not lend themselves to it. First and foremost, it is about the encounter. It is very difficult, I admit. We must protect the communities from flies, from predators. Unscrupulous designers and entrepreneurs who want to make a profit, bad tour operators who folklorize and distort, rephrase gratification and consumerism to satisfy a fleeting trend, and commodify a place or a site…

ST: … it could even prove dangerous, in the sense that it can create a tension that can ultimately have repercussions on the villagers. The visitor could feel taken hostage, even abused, given the contrast between his bill and the modern conveniences that may be lacking.

SN: Unfortunately it happened that some of these operators sabotaged projects that we had set up with the village women’s cooperative as well as the children’s awareness project. In the name of a so-called equitable approach. The truth is disturbingly cynical: the tour operator collects this sum without offering anything in return to the poor people of this village, and sets such a precedent that it becomes obscene and creates new social divisions and frustration. In the long term there is a risk of having a rejection of the tourist, bearer of evils.

All the while we must educate people to receive the other. And vice versa for visitors, we must prepare them, accompany them, circumstance them. We must also always revisit, inquire, speak with the people of the place. Look, I sacrificed a lot to save places and intangible practices that are then divested by this unscrupulous tour operators busy doing “pop-up” and their only relation to these people as that they serve merely as cogs in their binary system. This is clearly no more than divesting and perverting.

To enable true fair tourism there is a financial limit that must not be crossed and there must be a minimum of respect, not relationships of extraction colonialism. A charter of communal work should be decided together. We have even conducted small experiments where there was a reception of foreign guests at the homes of local families in the villages of a granary and exchange between students and the inhabitants trying to have a balance of income in the whole village so as not to create jealousy between the villagers. Topics were raised: of a project of restoration here, of equipment for a well there, etc.

ST: In this case, my question is: in a context where visitors pass through these ksours and ighrems of southern Morocco and feel inspired to help, or rather to contribute in their own way so that these communities pervade, how can we avoid pure financial donations ?

ST: We should never just hand out cash, but rather support real actions with conscientious people and avoid middle men. If we give money, we must follow it, know where it goes. For example, we can help schools, not by buying schoolbags but rather by training, by organizing workshops. Money is often a double-edged sword. It takes years to grasp the role of each person in a community. Take the example of the earthquake. A lot of money was doled out, how can we know it will be allocated justly ? Yet actions have been carried out on a human scale, where it is not always a question of funds. Yes, we could aim to expand our small conservation association, but that would entail a loss of flexibility and human scale.

We can also take a book caravan. Bring in eye doctors, dentists, etc. In conclusion, for the dignity of people, there must be a minimum of encounters and a minimum of trust that is built. In Europe, the government has incentivized people to maintain their heritage. In Morocco, there is always a balance to be taken into account that is very easy to disturb. We must quantify our actions and their reach and be wary of middlemen.

ST: It also hinges on us, as an agent, to filter the visitors and match the locations with their expectations. These tracts with their unique climatic and cultural conditions do not lend themselves to everyone.

SN: … it’s true, our lives are spent ‘educating’ each other. Respect must go in all directions. Who am I to pass judgment on people who could welcome me with a Kalashnikov in another country? Besides, we have trivialized travel, by sublimating only the fun, the gratification and ignoring the other side, which is to question oneself. One’s lack of prejudice. It also conditions those of us that can be bothered, to open our eyes to things, especially when they vanished elsewhere.

Moroccan hospitality has always been unique. In the most deprived regions or corners, you will never be let down. During our projects, we heard stories of tourists lost in the mountains arriving in these scattered villages. The locals rescued them and took care of them with the few means they had. Give and you will be given – it is deeply Moroccan.

ST: In the era of instant information and Artificial Intelligence, why is it important to preserve the culture of these regions for future generations?

SN: For its contrast. We are growing frustrated of this life run by machines. People ultimately crave real life, not virtual networks. They yearn towards things that bring them together, things that are perfect-able. Artificial intelligence is not life. It does not give meaning to life. Education and mutual respect are the keys to any encounter. In the name of modernity, we often destroy and transform irreversibly. When it is too late, people understand they were careless, but it is too often irreversible. I was in Japan recently, what impressed me most was people’s autonomy up in the mountains – their awareness of being in a healthy world, for their daily meals in particular. I think this model is the best: respect what is local, work to encourage specificities: a “real” bread, made with local flour and baked in a local oven in front of you, is a simple example of that.

* Max Weber – Charisma and Disenchantment

Translated from French by Cristian Martinus with help from Pamela Lalonde.

1 % of our income is donated towards social projects of Morocco since 2014. Some of those funds have gone towards the restoration of some of the granaries. We’d like to thank all our previous guests for making that possible.

On Salima Naji:

For over 20 years, the DPLG architect (École nationale supérieure d’architecture de Paris-La-Villette), Salima Naji, doctor in social anthropology (École des hautes études en sciences sociales in Paris), has been involved in numerous projects to protect oasis heritage.

In 2004, she founded a studio in Morocco specializing in the innovative use of sustainable raw materials and bio-sourced technologies (earth and stone, palm fiber). She has designed, restored or built over 30 bioclimatic buildings in raw earth and stone (maternity wards, boarding schools, women’s centers, museums, eco-lodges or hostels, etc.) At the same time, we support the development of eco-design activities for women and children. These workshops are regularly organized by facilitators trained by speakers from the Gardiens de la Mémoire association. The workshops for women help to promote local knowledge but also to develop new products. Children’s workshops complement school time and offer children creative activities. These activities also aim to allow children to understand earthquake-resistant architecture and architecture adapted to global warming.

Since the 2023 earthquake, the architect will begin to restore some damaged villages and take care of certain monuments. Other reconstruction programs also call on her services. The project aims to restore historic villages affected by the earthquake of October 8, 2023 by training the workforce in historic earthquake-resistant techniques. The goal is to restore a sense of community to the affected villages, as was the case in Agadir Ouffella.

Her practice is coupled with scientific activity in many international action-research programs that question sustainability and the deep relationship between societies and their environment. She has been a member of the scientific committee of the Berber Museum of the Majorelle Garden (Fondation Yves Saint-Laurent-Pierre Bergé Marrakech & Paris) since its creation in 2011 and has developed an important reflection on cultural mediation and the transmission of heritage, she has published numerous architectural works. She has published numerous works, both in academia and for a wider audience. She has been selected twice for the Aga Khan Award for Architecture (2013 and 2022).

© Sun Trails 2024. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher.