Fes, the cradle of Moroccan culture. Some say it’s stuck in time. It hasn’t changed. Some compare it to Marrakech, seen as dynamic, cosmopolitan, hedonistic even. With the passage of centuries, the milennial medina and its renowned university, akin to its sister- city across the Mediterranean, Granada, has had its share of visitors and chroniclers. Since first visiting in 2009, we’ve returned quite a few times. Did it change in the meantime ? Not that we noticed. But then, maybe 16 years is not that much in the grand scheme of things. Out of all its visitors, Titus Burckhardt visited Fes and even helped with its rehabilitation in the 1970’s. His rendition of the visit betrays a deep affection for Fes. It also evinces, bar the satellite dishes, how little has changed in the meantime.

{ All below photos were taken by Sun Trails team over the last 10 years. }

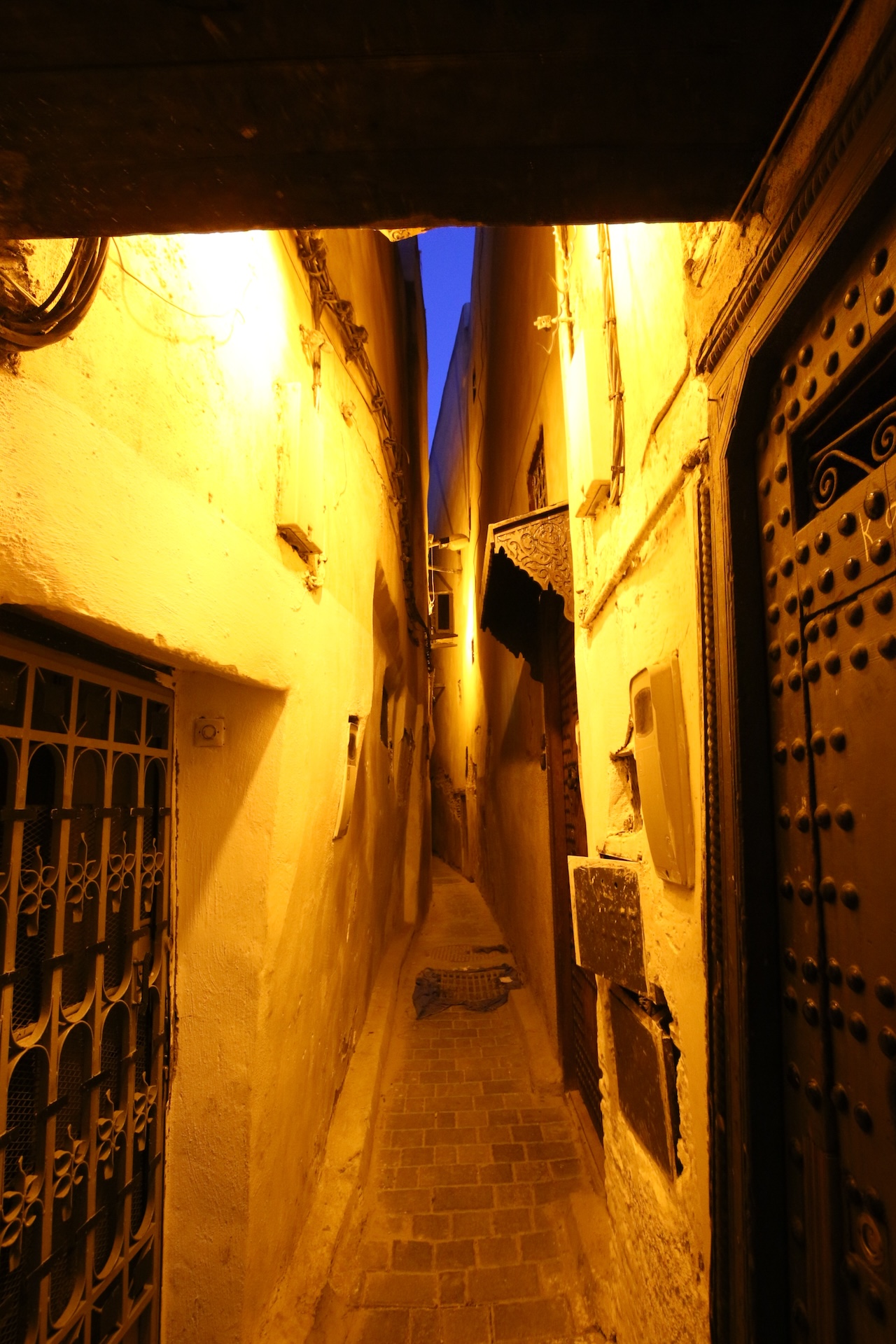

A geode of amethyst, brimful of thousands of tightly packed crystals and surrounded by a silver green rim: this was Fez, the old city of Fez in the twilight . As we came downhill towards it, the hollow in which it lies grew visibly larger; the countless crystals, uniform in themselves, but irregularly grown into one another, now came more clearly into view; one side of them was light while the other side, the one facing the prevailing wind, had become darkened and weather-beaten.

In the heart of the city, in the lowest point of the hollow, one could make out the tent-shaped roof of green glazed tiles that covers the dome of the tomb of the holy Idris, the founder of Fez; nearby was a minaret. Not far away where the equally green roofs of the old Quranic College of al- Qarawiyin. The nearer we came to the city the more minarets rose to Heaven, clear-cut, square, flat-topped towers similar to the Romanesque city towers of Italy. There must have been hundreds of them.

I asked myself whether the Old City might have inwardly changed during the twenty five years that I had been away from it. It still looked at the same as before: ancient, weather-beaten, withdrawn inside its walls.

The city was getting nearer, and at the same time it loomed up within my own mind, rising out of the darkness of memory, with all of its thousand faces pressing upon me questioningly. For Fez had once been familiar to me, well known and yet full of inexorable secrets. It was a city that had had to yield to foreign rule, and that had accepted in silence the arrival of a new order dominated by the power of machines, yet inwardly it remained true to itself.

Here indeed was Fez: the scent of cedar wood and fresh olives, the dry, dusty smells of heaped-up corn.

For at the time I first knew it, men who had spent their youth in an altered traditional world where still the heads of families. For many of them the spirit which had once created the Mezquita of Cordoba and the Alhambra at Granada was nearer and more real than all the innovations that European rule had brought with it. Since then, however, a new generation had arisen, one which from its earliest childhood must have been blinded by the glare of European might and which in large measure had attended French schools and thus henceforth bore within it the sting of an almost insuperable contradiction.

It was thus not without some anxiety that I returned to the familiar city, for nothing could be more painful than the site of a people robbed of its best inheritance in exchange for money, haste and dissipation.

In front of the city gate there was still the neglected cemetery with its irregular crop of graves between mule tracks and flowering thistles, where children were playing on white slabs and, here and there, man sat silently waiting for sunset and the call to prayer.

Just then the last pink glow on the towers disappeared. The sun had completely set and now only the green-gold of the sky shed a mild, no-shadow-forming light, in which everything seemed to float as if weightless and somehow glowing in itself. At that moment the long drawn-out call to the sunset prayer rang out from the minarets. One could see both individuals and groups spread out their prayer mats and turn towards the southeast, the direction of Mecca. Others hurried through the city gate to reach a mosque, and it was with the latter that we ourselves entered thre city.

We were immediately enveloped in the half-light of the narrow streets which descended steeply from the various gates into the hollow where the great sanctuaries lie surrounded by the bazaars or commercial streets – souks. In the streets all that can be seen of the houses are the high walls, darkened with age, and almost entirely without windows. The only open doors are those of the fanadiq or caravanserais, where peasants and bedouins visiting the town leave their steeds and beasts of burden in open spaces, surrounding a courtyard, and where on the upper story they can hire a room to pass the night or store their wares.

Otherwise, the street is like a deep, half-dark ravine which turns unexpectedly, sometimes here, sometimes there, often covered in by bridges from one building to another and only wide enough to allow two mules to squeeze past each other. Everywhere the cry Balik! Balik ! take care ! take care ! rings out. Thus do the mule drivers and the porters with heavy loads on their heads make their way through the crowd.

Only further down do the shops begin, where the traveler on arrival may find his necessities; there too are the saddlers, the basket-makers, and the cookshop-owners, the latter preparing hearty meals on little charcoal fires. We proceeded past them into the street of the spice-dealers Souk Al Attarin, which runs through the entire town center, and in which one shop lies hard against the next, a row of simple plain boxes, with shuttered doors in front, just as in Europe in the Middle Ages and with no more space than will allow the merchant to sit down amongst his piled up wears.

Nothing stirs the memory more than smells; nothing so effectively brings back the past. Here indeed was Fez: the scent of cedar wood and fresh olives, the dry, dusty smells of heaped-up corn, the pungent smell of freshly tanned leather, and finally, in the Souk Al Attarin, the medley of all the perfumes of the Orient- for here are on sale all the spices that once were brought by merchants from India to Europe as the most precious of merchandise. And every now and again one would suddenly become aware of the sweet smell of sandalwood incense, wafted from the inside of one of the mosques.

Equally unmistakable are the sounds; I could find my way blindfolded by the clatter of hooves on the steep pavings; by the monotonous cry of the beggars who squat in the dead corners of the streets; and by the silvery sound of the little bells, with which the water-carriers announce their presence when, wending their way through the souks, they offer water to the thirsty.

To the right of the Spice Market, just beside the Sepulchral Mosque of Idris II, the holy founder of Fez, there is a cluster of narrow passages lined with booths. Here all kinds of clothing are on sale: colored leather shoes, ladies’ dresses in silk brocade embroidered in gold and silver. Near the mosque there are also decorated liturgical candles, frankincense and perfumed oils.

Around the Sepulchral Mosque of the holy Idris there is a narrow alley, made inaccessible to horses and mules by means of beams. This constitutes the limits of the sacratum within which formerly no one might be pursued.

In the streets surrounding the Qarawiyin mosque the advocates and notaries have their little offices and the booksellers and book-binders have their shops- just like their Christian colleagues of old in the shade of the great cathedrals. As we passed by, we stole a glance through several of the many doors of the mosque and gazed into the illuminated forest of pillars, from which the rhythmical chanting of quranic surahs could be heard.

Then through the districts of the coppersmiths, where the hammers were already at rest and only here and there a busy craftsman still polished and examined a vessel in the light of his hanging lamp; soon we reached the bridges in the hollow of the town and ascended from there to the gate on the other side the Bab Al Futh. As we looked back we saw the old city lying beneath us like a shimmering seam of quartz. I now knew that the face of Fez, the old once familiar and yet foreign Fez, was unaltered. But did its soul live on as formerly ?

On one of the following evenings we were invited home by a Moroccan friend, to a house which, like all Moorish houses, opened only onto an inner courtyard, entirely white, where roses grew in profusion and an orange tree sparkled festively with blossoms and fruits. The room on the ground floor, where the guests sat in threes and fours on low divans, opened onto the courtyard. Amongst all the men present, there was also a small dark-skinned Arab boy. The master of the house told us he was the best singer of spiritual songs in the whole country. After the meal he invited him to sing to us. The boy shut his eyes and began, softly at first, and then ,gradually more loudly, to render a qasida, a symbolical love song.

And some of the guests who had gathered near him and had drawn back the hoods of their jallabas sang the refrain in a harsh ancient Andalusian Style. The Arabic verses of the poem grew faster and faster, in a quick intense tempo, while the answering refrain surged forth in widely extending waves.

All of a sudden the volume of the chorus, which until then had only answered the singer, flowed on without interruption and branched into several parallel rhythms, above which the voice of the leading singer continued at a higher pitch, like a heavenly exaltation above a song of war.

This was Fez, unalterable, indestructible Fez.

In 1972, UNESCO, together with the Moroccan government, delegated Titus Burckhardt to Fez to take charge of the plan for restoration and rehabilitation of the medina and its religious patrimony, as well as its handcrafts. Over the three following years he led an interdisciplinary team tasked with establishing a master plan for the rehabilitation of the monuments and the urban fabric, including handcrafts “whose role is to create an ambiance that allows spiritual values to shine through.